“The Two Jewish Neighborhoods of Aleppo”

From the book “A Social and Cultural Drama in Mandatory Aleppo”

Research by Professor Zvi Zohar

The community of Aram Zoba, also known as Aleppo, has a long and unique history. Its origins date back to ancient times, and its end came just a few years ago when the last of its members were allowed to leave Syria. It is difficult to speak of its true end, as the descendants of the Jews of Aram Zoba have established communities in New York, Mexico, Panama, São Paulo, Buenos Aires, and other places, where traditions, customs, prayers, and melodies have been preserved as they were passed down through the generations. Those with imagination can close their eyes in one of these Aleppan communities and feel as if they are still in the neighborhoods of Bahsita or Jamiliya, where the Jews of the community were concentrated in the final chapters of its life.

The community of Aram Zoba underwent many transformations throughout its long history. From a Romaniote community speaking Greek under Byzantine rule, it transitioned to Arab rule and the Arabic language starting in the 7th century. For centuries, it was situated between two major centers—the Land of Israel and Babylon—sometimes leaning one way, sometimes the other, or even both simultaneously.

During the Middle Ages, the community absorbed Jews from the East and West, including Ashkenazi and French Jews, Provençals, and Italians. After the expulsion from Spain, Sephardic Jews arrived in the city and created a parallel, even competing, congregation alongside the Musta’arabi Jews, who had coexisted for generations, sometimes clashing but in recent times began to merge. Until World War I, when the border between modern Turkey and Syria was established, the community of Aram Zoba served as a spiritual-religious and economic-commercial center for all the communities that remained within Turkey after 1923, and in the case of Iskenderun and Hatay, after 1938. These communities included Antep (Gaziantep), Urfa, Kilis, Mersin, Mardin, and others. The unfriendly border struck the status of Aleppan Jewry after the opening of the Suez Canal had already undermined the community’s economy, and emigration significantly weakened its demographic, economic, and religious strength. At the beginning of the century, the spiritual-religious center of Aram Zoba Jewry moved to Jerusalem, where many of its sages settled.

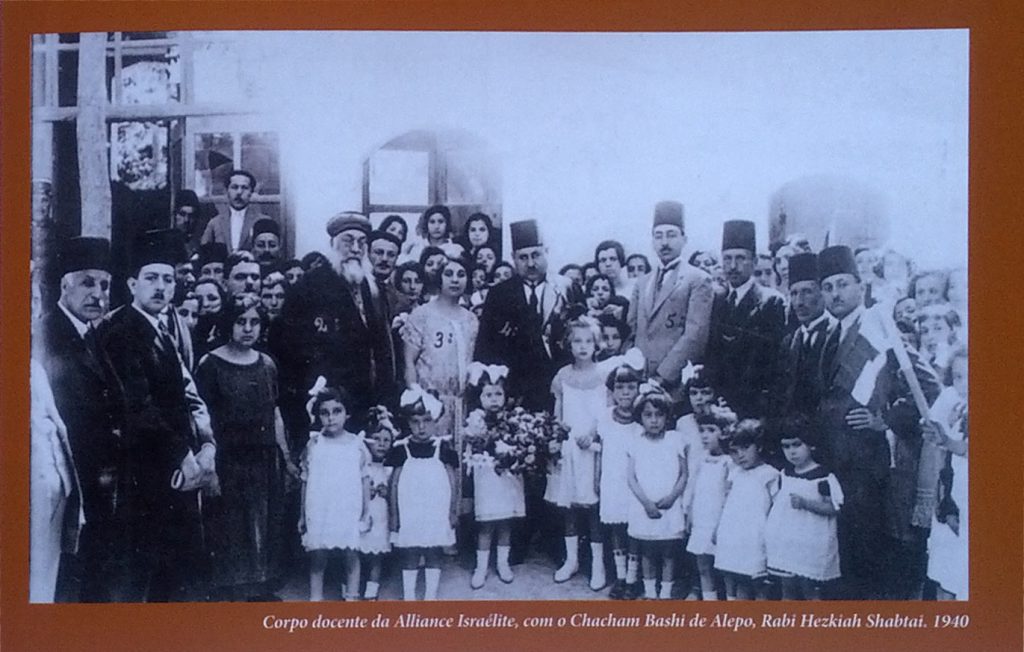

A new spirit swept through Aleppo with the penetration of Western influence from the second half of the 19th century onward. Both the Alliance Israélite Universelle and missionary schools influenced cultural and religious life, introducing a new language, French, and new subjects in science and literature to the youth of the community, who were exposed to modernity. The sources brought by Professor Zvi Zohar, accompanied by introductions, notes, and explanations, present the reader with various aspects of how the community and its sages confronted new challenges, challenges faced by the Jews of Aleppo and all Jews in the modern era—community and its challenges, community and its struggles. This publication aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the processes that affected the Jews of Aleppo and were experienced by all Jewish communities, sooner or later, in the modern era.

Until the last decades of the 19th century, almost all Jews of Aleppo lived in the old city, in an area centered around the Bahsita quarter. At the initiative of Ottoman governors from the Tanzimat period, the government developed land areas west of the old city, designated them for modern residential neighborhoods, and encouraged affluent individuals to build homes there. One of these neighborhoods, located about a kilometer northwest of Bahsita, was the Jamiliya quarter. Gradually, from the late 19th century onward, all Jews who could afford the move relocated to this area. From then on, the Jews of Aleppo were divided into two neighborhoods with distinct socioeconomic characteristics. The Alliance school for boys was located in Jamiliya. When the Alliance school for girls was established in 1894, it was also located in the same neighborhood. Abraham Elmaliach wrote in 1920:

“The Jews of Aleppo have a beautiful suburb outside the city, built in European style. Its houses are spacious, surrounded by gardens and orchards; it is ‘Jamaliya Street,’ named after the Turkish governor Jamal, who ruled Aleppo many years ago and sold this large plot to the Jews to establish a beautiful Hebrew neighborhood. In this neighborhood, you will find all the Jewish aristocracy, the Alliance schools, synagogues, etc.”

Tuition was required at both Alliance schools, and only a few students received scholarships. For this reason, as well as their location, almost all the students came from families with middle to upper-income levels. Thus, it was the children of parents who already enjoyed a relatively good economic standard of living who also received a modern French-Jewish education. Some parents in Jamiliya preferred to send their sons to traditional Talmud Torah schools rather than to the Alliance, while others sent them to non-Jewish French schools, whether of the Mission Laïque or various Christian orders. In 1922, an Alliance school for girls was established in Bahsita, emphasizing vocational education; however, attempts to establish a boys’ school there faced obstacles. As a result, most parents in Bahsita were spared the need to choose between different educational alternatives for their sons, as the main alternative to Talmud Torah was the missionary school. Therefore, almost all the children of Bahsita continued to study in traditional Talmud Torah schools, even during the Mandate period.

Thus, in addition to the economic gap between the residents of the two neighborhoods, there was also an educational and cultural gap. As Pinhas Ne’eman wrote in 1927: “Just as the social gap between the two classes is vast, so too is the cultural gap between them.” This gap had many implications, one of which was in the field of migration.